LERUP, Lars, 2001 : The frontier / Museum Geography, in After the city, Éditions MIT PRESS, p156.

|

GRIGONE Lasma LERUP, Lars, 2001 : The frontier / Museum Geography, in After the city, Éditions MIT PRESS, p156.

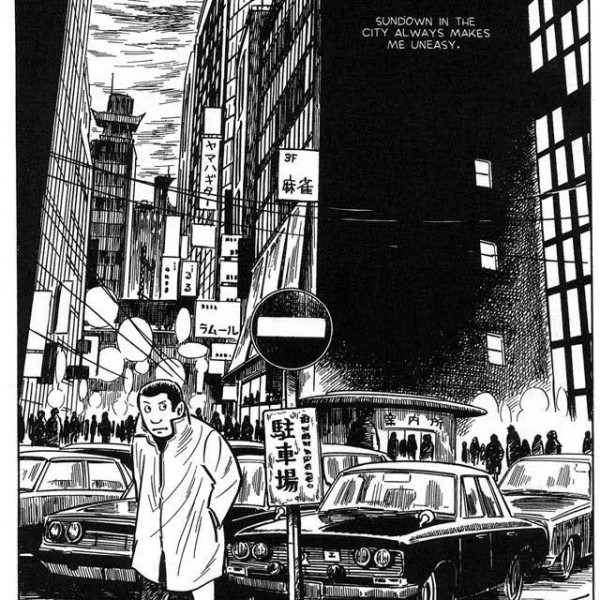

The city’s reign over our senses, our moods, our very ways of being is outmoded. The suburban metropolis has superseded the city. The new building materials are non-material: electricity, telephony, weather, time, and so forth. Consequently, according to Lars Lerup, architecture and architects must be rethought.

Until now, architects have been trained to serve the elite few, as reflected in a belief in customization and the uniqueness of each project. Architectural educators should promote teamwork and the design of authorless objects, combined with an integration of design and practice. Before we can rethink the architectural curriculum, however, we must rethink the metropolis.

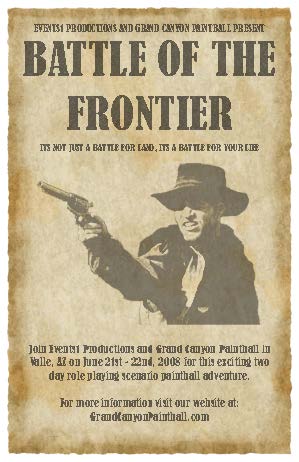

Unlike the many who view suburbia with paranoid dismay, Lerup takes an optimistic view of the new, open metropolis—for him not the site of unavoidable uniformity and mediocrity, but an exciting new frontier.

FRONTIER

The stretch of urbanity between Downtown and the suburban enclaves is motionless in the dense summer heat. The large territories of empty space, regularly interspersed with the built areas, are teeming with nature. The black parking pools of asphalt – the Strands of Hell– boil.

Very recently after decades of inaction, a new, most unlikely frontier has arisen: The NIMBYS (Not In My Back Yard), now reaching a logical conclusion in the BANANAs (Build Absolutely nothing Anywhere Near Anyone). The relationships between frontiers and the new metropolis are synthetic and inscrutable. To begin to search this surface to the most vibrant frontier, we must turn to mega shapes and to their internal characteristics, their ecology.

Most metropolitan regions consist of a series of very specific sub ecologies. In our case “Cite d’Architecture” that we are going to create south-west from the city center is going to really different “city ecologie“. The question to think about is- how it will work together with all the other ecologies around.

It is also evident that in some stages of the evolution of downtown it has been seen as a frontier. But this in no longer the case- the city is spreading and triangle COURS GAMBETTA/ BD RENOUVIER/AV CLEMENCEAU is already almost the center. And improvements in public transport (with tram3) will make the distance between these regions relatively even smaller. The location our project is in very chic, prior and privileged place. Middle landscape (middlescape) – half city, half nature – is now being introduced. An almost intact grid of streets organizes the middlescapes (spaces in the middle) into technocratic ledger open to speculations. Yet opposing forces, paths, and habits counteract a too simplistic interpretation.

That is exactly the situation that arise in our lot, because road is creating space in the middle, which is open to different interpretations, expositions and activities. Joining the quarter is our prior task. Although an image of utter tranquility, the middle landscape is deceptively homogeneous. This deception is partially maintained because of our own blindness. This is as if everything, despite its profound and deep difference, is painted, if not in the same color, at least in the same hue.

MUSEUM GEOGRAPHY

BERLIN, Museum Insel. Distinct urban shape and location, but more an atmosphere. Slightly higher densities, occasional large buildings, some semi-public spaces and Modern Architecture, but no perspectival presentation, no network of boulevards, no civic conclusions, no public plazas. This district is a grain, offering a certain level of discrete pattern recognition. Located between Medical center and Downtown, it has no precise borders. As in sprawl, the seekers have to do some work to find their prey.

Similar situation as in our district – located between “Musee du CORPS HUMAIN“, EAI, ECUSSON and suburbs of the Montpellier. Just we are not making “Museum island” – but the “Island of and for architecture“.

“Public space” in the suburban metropolis is not the plaza of the city, but a peculiar blend of (propre mélange de) software and hardware, more vapor than pavement, more dynamic then stable, because bound to events rather than manifested by places.

The key to the creation of a public dimension in the Museum District is to realize that the local citizen- the families of the working force of the global production apparatus- must be the part of museum world. The sculpture garden at the Museum of Fine Arts may have various publics – dog owners, wedding parties, mothers with young children – that use them frequently but have yet to enter museum. These publics may never be fully integrated, but, by existing side by side they are integrating.

There are several interesting attempts to assembly the publics- a basketball court next to the museum may help construct occasions in which the elegance of the game meets the beauty of the painting.

The reasons are not just to build connections, but to see these as crucial access points in making larger, more powerful external spatial flows. The principle is to break down barriers as well as building relations. Broken barriers widen the scope, without deflecting the narrow purpose, and force various participants to work together.

We should look forward to prospects of making the entrepreneurial concept of spatial flows successful, socially and economically.

LERUP, Lars, 2001 : The frontier / Museum Geography, in After the city, Éditions MIT PRESS, p156.

|